Entry 9: Mean Girls

October 31, 2025

NOTES FROM THE BALCONY, ENTRY #9

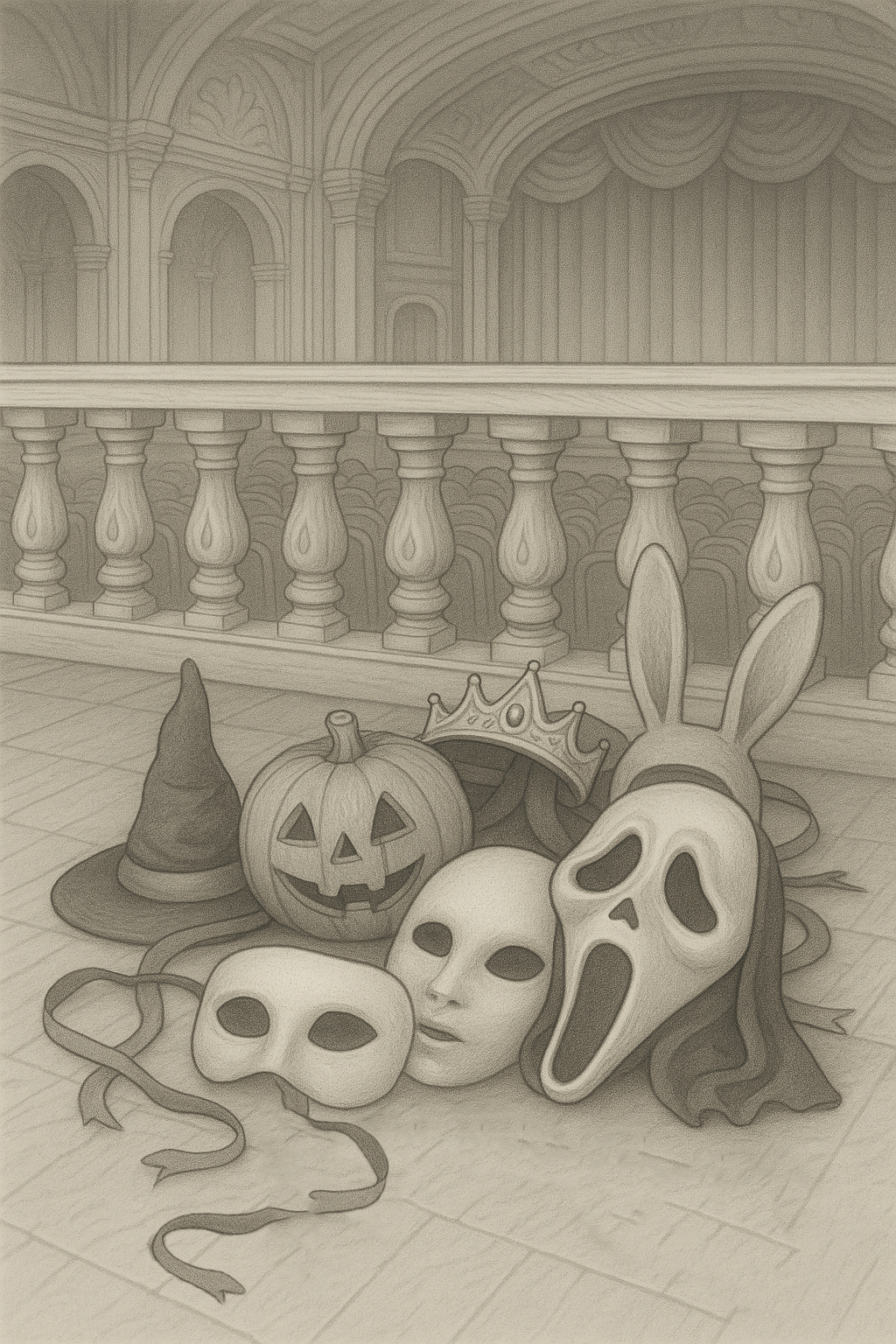

Masks aren’t just for Halloween

*Author’s note: If you’re waiting on Shifting Gears (Part 2), it turns out my car is taking forever to make it up the street. It barely runs. For now, let’s take a moment to indulge in the tricks and treats that come with this season. It’s time for Notes From The Balcony, Entry 9: Mean Girls.

On this crisp October evening, our balcony is lit by the hypnotic orange flicker of jack-o’-lanterns from the street below. Not a chapel, bedroom, or even an art studio — tonight we land on an observation deck. Choose a seat, here, you can even sit next to me. And it's not Wednesday, so don't worry about your outfit.-Trick-or-treaters move in packs, candy buckets swinging, their chatter rising like a tide from all sides. From up here, I can’t help but think of that party from back in '04 — the one where a single costume choice split the night open, where the term "mean girls" became shorthand for every unspoken rule of belonging, even beyond high school. Watching the costumed crowd drift by, it’s easy to remember these roles aren’t locked to adolescence. They slip on and off throughout our lives, worn in offices, coffee shops, even in so-called dedicated circles of healing. Tonight the street becomes my camouflage and mirror — every mask carrying the same fragile lesson: that sometimes survival can hinge on belonging.(I’m a mouse, duh) Still from mean girls, Released 2004 by paramount pictures

I set a red solo cup on the edge of the kitchen counter, almost falling off. Tracing my two fingers beneath its smooth bottom, I apply drunken physics logic to a strategic flip of the cup, hoping it will land cleanly on its opposite side. Fail. Go, fail. Go! Okay, go, go, go! I turn and shout to my friend Lauren. She isn’t paying attention, laughing way too hard at some guy in a full-sized yellow Care Bear costume covered in smudges of dirt and who-knows-what, as he occasionally lifts his fake bear head to take a drink. It’s totally like something out of a child’s nightmare. The guy across from me wears a D.A.R.E. t-shirt with intentional irony, catching my attention and I burst into laughter now too and the whole room has lost control in a great way like what sometimes happens at parties. Everyone smells like cheap vodka and Coke, a gross combination, and the music is so loud it steals your ability to think. The not-thinking aspect is part of the appeal, which is why we’re all here in the first place. This frat house is a frequent haunt of ours, and I’d consider us certified groupies.

It was a common scene for us—winding up somewhere on Duryea with a whole tray of special brownies in tow (sometimes still warm from the oven), and stars of hope dazzling our eyes and blinding us to the reality of why we were there in the first place. The beginning of my college experience was less about where I was and more about where I had been. At the center of my prolonged mid-week outings and general off-the-wall behavior was my need to ricochet completely in the opposite direction of whatever high school had represented for me. That representation, I would now describe as: shifting from desperately wanting to fit in with the perceived “cool girls” in my early teens to really and truly not caring by the time we hit graduation. These girls, the ones with acrylic nails and professionally-dyed hair...they were not interested in being my friend, they just wouldn’t say it to my face. I know many women like that even now, in my mid-thirties. I still want to escape them, but I also remember that many of them are living within the constraints of fear. This is usually the fear of being authentic, as people of ten relate true authenticity with the qualities of being “weird” or “strange”.

I know some must have had it far worse than I did. I got along with most groups and we had enough money to buy whatever was on trend, but I never felt good enough, never felt like the “it” girl. I remember this girl Courtney, she had these corduroy clogs from Old Navy that she would wear with her perfectly and strategically-ripped Abercrombie jeans. She always smelled like their perfume too. One day I came to school wearing those same clogs, and I never saw her wear them again. Why not?

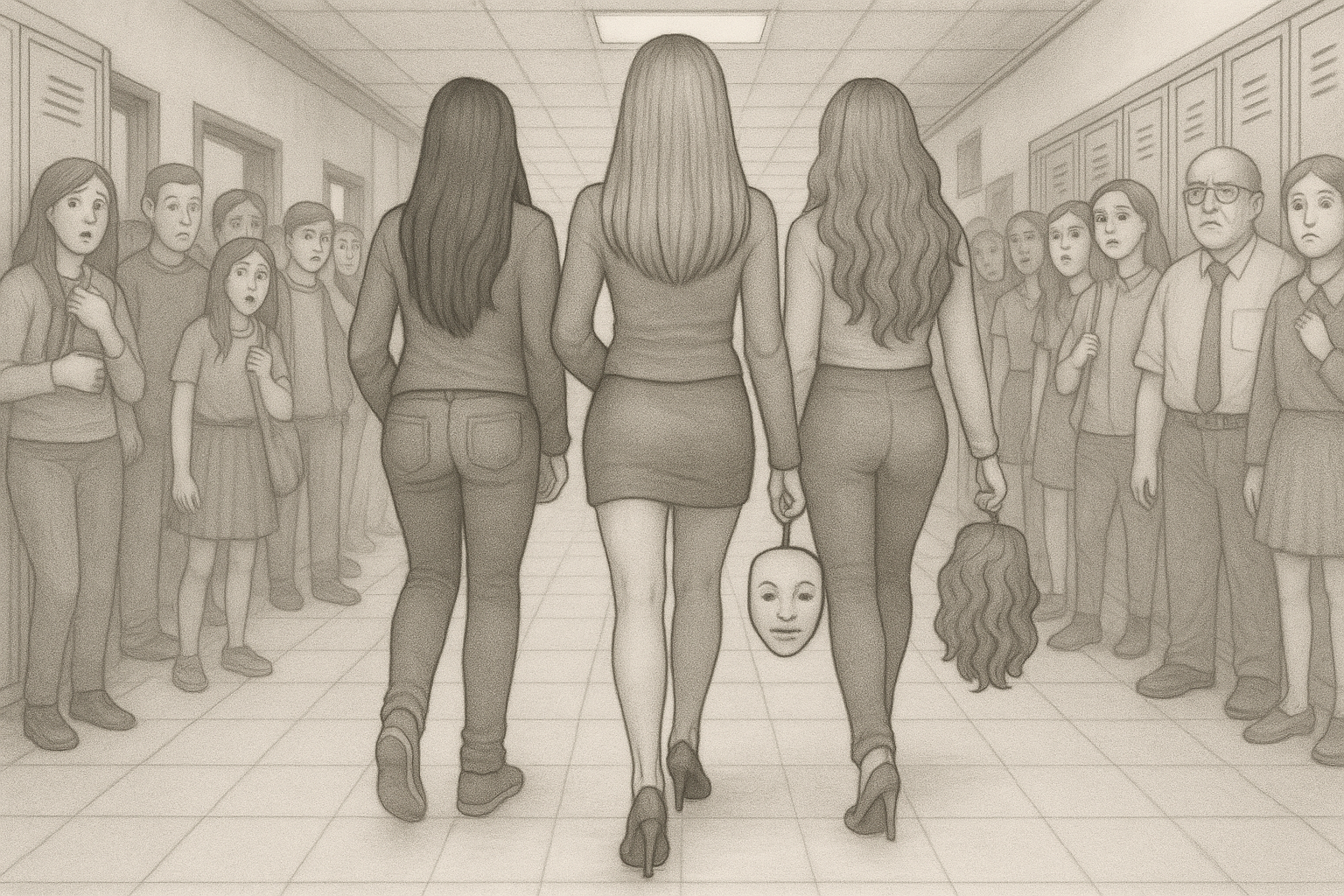

Back at the party, we are witnessing every mean girl archetype that ever existed, the first being the queen bee herself. In this case, she is dressed to the nines in a silky white corset and matching bunny ears. She looks you up and down, silently, your presence in the space is pending her approval.This girl is easy to spot. She moves through the hallways like she owns them, a glossy hurricane of hair, perfume, and perfectly sharpened barbs. Her beauty is curated, her smile rehearsed — the kind of grin that dazzles teachers but slices peers to ribbons. Her laughter rings loudest at someone else’s expense, a chorus of approval trailing behind her from those desperate enough to orbit her flame. She is power in a plaid skirt, a master at weaponizing charm, cruelty, and social hierarchy. One word from her can crown you a queen for the week or exile you to cafeteria oblivion. She doesn’t just thrive on attention — she engineers it, manipulates it, feeds on it. Beneath her flawless exterior lies a ruthless strategist who knows the value of secrets, the leverage of humiliation, and the intoxicating rush of control.In her lengthy shadow stands our next archetype: the "best friend", the one dressed as a leopard cat, black spandex and all. Her laughter is just a little too loud, her insults a little too forced, her clothes like a secondhand copy of the original. She studies the real mean girl the way others study textbooks, memorizing the tilt of her head, the cadence of her cruelty, the way power can drip from a single raised eyebrow. But imitation never makes her equal.

What makes her dangerous isn’t her influence — it’s her hunger. She wants the throne so badly that her every move seethes with resentment. She envies the ease with which the queen commands attention, envies the unearned loyalty of the entourage, envies the effortless sparkle of authority that she herself can only mimic. And because she’s not the real thing, she burns hotter, sharper, meaner — cruelty without charisma, venom without polish. She’s not worshipped; she’s feared in the wrong way, the way a desperate dog is feared when cornered.

In the end, she’s a tragic kind of villain: forever clawing at a crown that was never hers, forever sharpening her tongue on the bones of friendships she’ll never keep. She isn’t the star of the movie. She’s the understudy who poisons the lead, praying the spotlight might finally hit her face.When I think about the archetypes of high school — Regina George, Laney Boggs, Kat Stratford, Tai Frasier — I don’t just see cliques and cafeterias. I see echoes of those patterns in adult life, at work, in community spaces, even in so-called circles of healing. The roles we played at sixteen are roles we return to, only dressed differently.

The “mean girl” energy is not always obvious. Sometimes it wears flowing skirts and speaks in a soft voice about energy and alignment. Sometimes it leads workshops or claims to create community. But the pattern underneath is familiar: attention as currency, belonging as a hierarchy, admiration as something to hoard. And when usefulness runs out — when your glow can’t be borrowed, when your story no longer feeds their platform — the warmth fades. The whispers begin. You become material for someone else’s narrative.

It’s not always malicious in the way it was at sixteen. More often, it’s hunger. A hunger to matter, to stay visible, to avoid the terror of being overlooked. That hunger can make anyone sharp, even those who started with good intentions. The cruelty of gossip, the quickness to criticize, the readiness to abandon — these are just modern versions of the same old choreography.

And maybe that’s what strikes me most: how fragile these roles really are. The queen bee, the imitator, the artsy outsider turned icon — all of them reveal how deeply we want to be seen, how much we fear being discarded. What feels like villainy in the moment is sometimes just another person’s panic at the thought of irrelevance.

The lesson, for me, isn’t to divide people into categories of good or bad, mean or kind. It’s to recognize the patterns as they show up, in myself and in others, and decide how much of that dance I’m willing to join.From the balcony, I see all these girls — not just in the street below but in myself. The queen bee, the imitator, the outsider, the rebel — they don’t vanish after adolescence. They flicker on and off like the jack o' lanterns, sometimes borrowed for a night, sometimes worn too long. Now those masks are digitized, pixelated, slipped on like filters. A computer screen becomes a costume, and suddenly the hallways of high school are infinite, sprawling across comment sections and feeds.

Who is behind the screen leaving those nasty comments? Who decides it’s easier to wound another woman than to confront the real structures that keep us all caged? The cruelty feels familiar: Regina with a Wi-Fi connection, Chris Hargensen with an anonymous handle. Keyboard warriors who’d never raise their voices in daylight but find a vicious freedom in the glow of the screen.

What breaks me open is the direction of the fire. Why are women still committing war against each other — rehearsing the same locker room battles in digital form — instead of sharpening our blades for something larger? Why do we keep clawing at one another while the orange-faced apes dressed in suit and tie sit untouched, their power unchallenged? From up here, it looks like misdirection: a trick that keeps us at each other’s throats so we never lift our eyes to the real enemies in the room, and we never get our treat.The plastics show up in every teen movie — the Regina Georges, Big Reds, and Chris Hargensens — strutting down the hallway with a smirk that could topple kingdoms. But the “mean girl” isn’t just a character on screen; she’s a pattern, a presence, a role we’ve all encountered. Maybe she once hugged you, and then broke your trust. Maybe she whispered your secrets to an audience. Maybe she’s on your next Zoom call. Maybe, if you’re brave enough to admit it, you’ve even played her part yourself. Aren’t we all just scared humans, wearing the many masks it takes to survive?

The truth is, “mean girl” is less a person than a costume anyone can wear. And once you start looking closely, you begin to see her everywhere.